The trade in gladiators was Empire-wide, and subjected to strict official control. Rome's military success produced an influx of soldier-prisoners who were redistributed for use in State mines or amphitheatres and for sale on the open market. For example, in the aftermath of the Jewish Revolt, the gladiator schools received an influx of Jews – those rejected for training would have been sent straight to the arenas as noxii. The best – the most robust – were sent to Rome. The granting of slave status to soldiers who had surrendered or allowed their own capture was regarded as an unmerited gift of life and gladiator training was an opportunity for them to regain their honour in the munus.

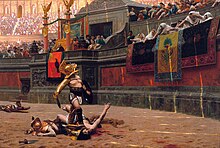

Pollice Verso ("With a Turned Thumb"), an 1872 painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme, is a well known historical painter's researched conception of a gladiatorial combat.

For those who were poor or non-citizens, the gladiator schools offered a trade, regular food, housing of sorts and a fighting chance of fame and fortune. Gladiators customarily kept their prize money and any gifts they received. Tiberius offered some retired gladiators 100,000 sesterces for a return to the arena. Nero gave the gladiator Spiculus property and residence "equal to those of men who had celebrated triumphs." Mark Antony promoted gladiators to his personal guard.

Female gladiators were also used, though archaeological evidence for them is uncommon.

Legal and social status

"He vows to endure to be burned, to be bound, to be beaten, and to be killed by the sword." The gladiator's oath as cited by Petronius (Satyricon, 117).The legal status of gladiators was unequivocal: they were slaves, and only slaves found guilty of specific offences could be sentenced to the arena. Citizens were legally exempt from this sentence but those found guilty of particular offenses could be stripped of citizenship, formally enslaved and dealt with accordingly. Freedmen or freedwomen offenders could be legally reverted to slavery. Arena punishment could be meted for banditry, theft and arson but above all, treasons such as rebellion, census evasion to avoid paying taxes, and refusal to swear lawful oaths.

Offenders seen as obnoxious to the state (noxii) received the most humiliating punishments. By the 1st century BCE, noxii were being condemned to the beasts (damnati ad bestias) in the arena, with almost no chance of survival, or were made to kill each other. From the early Imperial era, some were forced to participate in humiliating and novel forms of mythological or historical enactment, culminating in their execution.

Those judged less harshly might be condemned ad ludum venatorium or ad gladiatorium – combat with animals or gladiators, in which they were armed as thought appropriate. These damnati at least might put on a good show and retrieve some respect. They might even – and occasionally did – survive to fight another day. Some may even have become "proper" gladiators.

Modern customs and institutions offer few useful parallels to the legal and social context which defined the gladiatoria munera Under law, anyone condemned to the arena or the gladiator schools (ad ludum) was a servus poenae under sentence of death unless manumitted. A rescript of Hadrian reminded magistrates that "those sentenced to the sword" should be despatched immediately "or at least within the year". Those sentenced to the ludi should not be discharged before five years or three years if awarded manumission.

The phenomenon of the "volunteer" gladiator is more problematic. All contracted volunteers, including those of equestrian and senatorial class, were legally enslaved by their auctoratio because it involved their potentially lethal submission to a master. Nor does the citizen or free volunteer's "professional" status translate into modern terms. All arenarii (those who appeared in the arena) were "infames by reputation", a form of social dishonour which excluded them from most of the advantages and rights of citizenship. Payment for such appearances compounded their infamia. The legal and social status of even the most popular and wealthy auctorati was thus marginal at best. They could not vote, plead in court nor leave a will; unless they were manumitted, their lives and property belonged to their masters. Nevertheless there is evidence of informal if not entirely lawful practices to the contrary. Some "unfree" gladiators bequeathed money and personal property to wives and children, possibly via a sympathetic owner or familia; some had their own slaves and gave them their freedom. One gladiator was even granted "citizenship" to several Greek cities of the Eastern Roman world.

Among the most admired and skilled auctorati were those who returned to the arena having been granted manumission. Some of these highly trained and experienced specialists may have had no other practical choice open to them. Under Roman law, a former gladiator could not "offer such services [as thoses those of a gladiator] after manumission, because they cannot be performed without endangering [his] life."

Caesar's munus of 46 BCE included at least one equestrian, son of a Praetor, and possibly two senatorial volunteers. Under Augustus, senators and equestrians and their descendants were formally excluded from the infamia of association with the arena and its personnel (arenarii). However some magistrates – and some later Emperors – tacitly or openly condoned such transgressions and some volunteers were prepared to embrace the resulting loss of status. Some did so for payment, some for military glory and – in one recorded case – for personal honour. In 11 CE Augustus, who enjoyed the games, bent his own rules and allowed equestrians to volunteer because "the prohibition was no use". Under Tiberius, the Larinum decree (19 CE) reiterated the laws which Augustus himself had waived. Thereafter Caligula flouted them and Claudius strengthened them. Nero and Commodus ignored them. Valentinian II, some hundreds of years later, protested against the same infractions and repeated similar laws: his was an officially Christian empire.

One very notable social renegade was an aristocratic descendant of the Gracchi, infamous for his marriage (as a bride) to a male horn player. He made a voluntary and "shameless" arena appearance not only as a lowly retiarius tunicatus but in woman's attire and a conical hat adorned with gold ribbon. In Juvenal's account, he seems to have relished the scandalous self-display, applause and the disgrace he inflicted on his more sturdy opponent by repeatedly skipping away from the confrontation.

Emperors as "gladiators"

Caligula, Titus, Hadrian, Lucius Verus, Caracalla, Geta and Didius Julianus were all said to have performed in the arena (either in public or private) but risks to themselves were minimal. Claudius – characterised by his historians as morbidly cruel and boorish – fought a whale trapped in the harbor in front of a group of spectators. Commentators invariably disapproved of such performances.Commodus was a fanatical participant at the ludi, much to the shame of the senate — whom he loathed — and the probable delight of the populace at large. He fought as a secutor, styling himself "Hercules Reborn". As a bestiarius he was said to have killed 100 lions in one day, almost certainly from a platform set up around the arena perimeter which allowed him to safely demonstrate his marksmanship. On another occasion, he decapitated a running ostrich with a specially designed dart, carried the bloodied head and his sword over to the Senatorial seats and gesticulated as though they were next. He was said to have restyled Nero's colossal statue in his own image as "Hercules Reborn" and re-dedicated it to himself as "Champion of secutores; only left-handed fighter to conquer twelve times one thousand men." For this, he drew a gigantic stipend from the public purse. Perhaps to explain both his obsession and administrative incompetence, gossips suggested that his mother, Faustina the Younger, had conceived him with a gladiator.

Schools and training

Model of Rome's Great Gladiatorial Training School (Ludus Magnus).

Following the Spartacus Revolt and the political exploitation of munera, legislation progressively restricted the ownership, siting and organisation of the schools. By Domitian's time, many had been more or less absorbed by the State, including those at Pergamum, Alexandria, Praeneste and Capua. The city of Rome itself had four; the Ludus Magnus (the largest and most important, housing up to about 2,000 gladiators), Ludus Dacicus, Ludus Gallicus, and the Ludus Matutinus, which trained bestiarii.

Volunteers required a magistrate's permission to join a school as auctorati. If this was granted, the school's physician assessed their suitability. Their contract (auctoramentum) stipulated how often they were to perform, their fighting style and earnings. A condemned bankrupt or debtor accepted as novicius could negotiate for partial or complete debt payment by his lanista or editor. Faced with runaway re-enlistment fees for skilled auctorati, Marcus Aurelius set their upper limit at 12,000 sesterces.

All prospective gladiators – whether volunteer or condemned – swore the same oath (sacramentum). Novices (novicii) trained under teachers of particular fighting styles, probably retired gladiators. They could ascend through a hierarchy of grades (s. palus) in which primus palus was the highest. Lethal weapons were prohibited in the schools – weighted, blunt wooden versions were probably used. Fighting styles were probably learned through constant rehearsal as choreographed "numbers". An elegant, economical style was preferred. Training included preparation for a stoical, unflinching death. Successful training required intense commitment.

Those condemned ad ludum were probably branded or marked with a tattoo (stigma, plural stigmata) on the face, legs and/or hands. These stigmata may have been text – fugitive slaves were marked thus on the forehead until Constantine banned the use of facial stigmata in 325 CE. Soldiers were marked on the hand.

Gladiators were accommodated in cells typically arranged in barrack formation around a central practice arena. Juvenal describes the segregation of gladiators according to type and status, suggestive of rigid hierarchies within the schools: "even the lowest scum of the arena observe this rule; even in prison they're separate". Retiarii were kept away from damnati, and "fag targeteers" from "armoured heavies". As most ordinarii at games were from the same school, this kept potential opponents separate and safe from each other until the lawful munus. Discipline could be extreme, even lethal. Remains of a Pompeian ludus site attest to developments in supply, demand and discipline; in its earliest phase, the building could accommodate 15–20 gladiators. Its replacement could have housed about 100 and included a very small cell, probably for lesser punishments and so low that standing was impossible.

Despite the harsh discipline, gladiators represented a substantial investment for their lanista and were otherwise well cared for. Their high-energy, vegetarian diet combined barley, boiled beans, oatmeal, ash (believed to help fortify the body) and dried fruit. Compared to modern athletes, they were probably overweight, but this may have "protected their vital organs from the cutting blows of their opponents". The same research suggests they may have fought barefoot.

Regular massage and high quality medical care helped mitigate an otherwise very severe training regime. Part of Galen's medical training was at a gladiator school in Pergamum where he saw (and would later criticise) the training, diet, and long term health prospects of the gladiators.

Combat

Mosaic at the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid showing a retiarius named Kalendio (shown surrendering in the upper section) fighting a secutor named Astyanax. The Ø sign by Kalendio's name implies he was killed after surrendering.

Spectators expected a legitimate and definite conclusion to the munus. By common custom, it was left to the spectators to decide whether or not a losing gladiator should be spared and they also decided the winner in a "standing tie", though the latter was rare. Even more rarely – perhaps uniquely – a stalemate ended in the killing of one gladiator by the editor himself. Most matches employed a senior referee (summa rudis) and an assistant, shown in mosaics with long staffs (rudes) to caution or separate opponents at some crucial point in the match. A gladiator's self-acknowledged defeat – signaled by a raised finger (ad digitum) – told the referee to stop the combat and refer to the editor, whose decision would usually rest on the crowd's mood. During the match, referees exercised judgement and discretion; they could pause bouts to allow combatants rest, refreshment and a "rub-down".

The number of combats fought by gladiators was extremely variable. Most fought at two or three munera annually but an unknown number died in their first match. Up to 150 combats are recorded for a very few individuals. A single bout probably lasted between 10–15 minutes, or 20 at most. Spectators preferred well matched ordinarii with complementary fighting styles but other combinations are found, such as several gladiators fighting together or the serial replacement of a match loser by a new gladiator, who would fight the winner.

Victors received the palm branch and an award from the editor. An outstanding fighter might receive a laurel crown and money from an appreciative crowd but for anyone originally condemned ad ludum the greatest reward was manumission, symbolised by the gift of a wooden training sword or staff (rudis) from the editor. Martial describes a match between Priscus and Verus, who fought so evenly and bravely for so long that when both acknowledged defeat at the same instant, Titus awarded victory and a rudis to each. Flamma was awarded the rudis four times, but chose to remain a gladiator. His gravestone in Sicily includes his record: "Flamma, secutor, lived 30 years, fought 34 times, won 21 times, fought to a draw 9 times, defeated 4 times, a Syrian by nationality. Delicatus made this for his deserving comrade-in-arms."

1 comments:

Did you know that you can make money by locking special pages of your blog / site?

To begin you need to open an account on CPALead and run their content locking widget.

Post a Comment